Antarctica is approximately 50 times the size of the UK. It holds 90% of the world’s ice; enough to raise sea levels by 60 m if it all melted. Although Antarctica is a faraway continent, it has a direct impact on the rest of the world, including here in the South Hams.

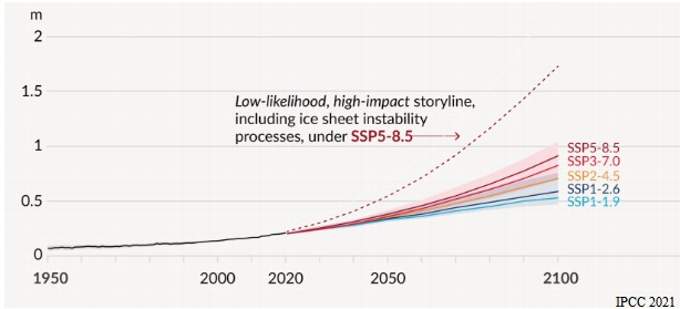

The chart (Pictured right) is taken from the latest IPCC report. The solid lines show sea level rise projections that assume only a small contribution from Antarctica, but the dashed line shows where sea levels will be heading if we see a greater contribution from Antarctica.

Scientists believe there is currently a 1 in 20 chance of a 2 meter increase in sea level over the next 80 years. This would mean that, within one lifetime, Slapton Ley would become a cove, our small coastal communities would have to be abandoned, and tidal barriers would be needed at Dartmouth and Salcombe. At present 410 million people in the world live within 2 meters of sea level, meaning we would face an unprecedented number of displaced people that would dwarf today’s refugee crisis. Even under low-emissions scenarios, sea levels are projected to continue rising after 2100, reaching +2m by 2300.

My research has focused on Antarctica during the last warm period in the Earth’s history. Differences in the Earth’s orbit 116,000 to 125,000 years ago meant that the globe experienced similar temperature increases to those we are experiencing now. We know from the geological records that peak sea levels were at least 6 m higher than they are at present and may have been 18 m higher. This means that Antarctica must have made a significant contribution to sea level rise in the past. If it happened before, it can happen again.

Known unknowns

Change in Antarctica does not occur at a steady rate. The ice can seem relatively stable, but once a tipping point is passed, change can suddenly happen much more rapidly. This makes predicting Antarctica’s future difficult, and it also fosters dangerous complacency. By the time we are seeing dramatic change, it will be too late to stop it and the ice loss will be irreversible.

In Antarctica, ice that equates to 20 m of sea level rise sits below sea level. Whereas ice that sits on the side of a mountain will respond to warmer temperatures by retreating up the mountain to cooler altitudes where it will- hopefully- stabilise, ice that sits below sea level retreats down, exposing more ice surface to warm ocean water, which causes further melt. This process of runaway melting is known as Marine Ice Sheet Instability. Studies suggest that this process may have already started in West Antarctica, but the rate of change depends on our ability to cut greenhouse gas emissions.

Although ice shelves are floating and so do not directly contribute to sea level rise, they act as buttresses that stop the ice sheet from collapsing into the sea. As the disintegration of the Larsen B ice shelf over a few weeks in 2002 showed, ice shelves can disappear very rapidly. Studies suggest that keeping warming below 1.5 degree is key to the survival of most of Antarctica’s ice shelves, and if warming exceeds 2 degrees, even the largest ice shelves, the Ross and Ronne-Filchner, are in danger. We have already passed 1 degree of warming.

Since Antarctica is such a remote and difficult environment to work in, as well as known unknowns, there could also be unknown unknowns that may come as an unpleasant surprise.

What can we do?

Protecting our coastal communities and infrastructure from rising sea levels needs to be treated with much greater importance and urgency at both local and national levels of government. Plans need to be in place to deal with the projected 0.5 to 2 m of sea level rise that will occur in coming decades. Although the amount of money required to build extensive flood defences is large in absolute terms, when compared to the value of assets and the size of population that will be protected, it is modest.

As well as defending our coastline, it is vital that we reduce our greenhouse gas emissions to keep sea level rise as low as possible. Over the past year, I have been chairing climate change roundtables hosted by my MP, Anthony Mangnall. We’ve spoken to experts across the country on topics ranging from restoring marine habitats, to the expansion of EV charging infrastructure, to improving the energy efficiency of houses in conservation areas. From these meetings, I am compiling a report that details practical steps that Westminster can take to help the Totnes constituency reach net zero by 2050. However, each meeting has also emphasised the fact that the actions of individuals and local communities have an extremely important part to play in reaching net zero.

Devon is fortunate to have the highest number of community energy groups in the country. They contribute £15 million a year to the local economy and their community energy funds directly benefit the local area. On a visit to the South Brent Community Energy Society last month, we discussed the possibility of all the community energy groups forming a Devon electricity supplier that would give us the opportunity to buy locally generated renewable electricity at a lower price than from national providers. Onshore wind turbines might not be everyone’s cup of tea, but they certainly beat being held to ransom by Vladimir Putin.

Making your home more energy efficient will save money as well as reduce your carbon footprint. The Cosy Devon scheme, run by the county and district councils, can offer free energy and money saving advice. The eligibility criteria is broad and includes people with long term health conditions, such as asthma, and the recently bereaved, as well as those on low-incomes. For those with older houses, Historic England’s website provides a wealth of free information on how to safely insulate old and listed buildings on a variety of budgets.

It is not just for the world’s politicians to solve this problem; we all have a responsibility to take care of the planet for future generations. Whatever happens on the global stage at COP26, we cannot underestimate the power of an engaged local community.

Dr Helen Millman is an Antarctic ice sheet modeller. She was born and brought up in South Brent, but gained her PhD in Climate Science from the University of New South Wales in Sydney in 2019. She will be attending COP26 as part of the International Cryosphere Climate Initiative.

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.